News & Blogs

Advancing environmental justice through legal empowerment – a collective learning journey

*Haz clic aquí para leer en español.

As we landed in Buenos Aires at the end of July for a week of events with Grassroots Justice Network members in the region, we were met by a cold, rainy winter day. Three days later, Buenos Aires -and many other parts of South America- were hit by a heatwave that brought us, in the middle of winter, to soaring temperatures.

The impacts of the climate crisis and environmental destruction in Latin America -and around the world- are undeniable. Whether it is unseasonal heatwaves and extreme temperatures like the ones in Buenos Aires, water scarcity, pollution, deforestation, destruction of ecosystems, etc. Historically marginalized communities across the region, such as Indigenous Peoples, Afro Descendant communities, women and girls, and urban poor communities disproportionately bear those impacts.

Despite being the most harmed by environmental destruction and climate change, and being the crucial stewards of our land and natural resources, these communities are continuously excluded from decision-making around environmental governance. Their experiences, knowledge, and priorities are disregarded. When they take action, they are often harassed, attacked, criminalized, or even assassinated.

With the support of the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and Global Affairs Canada (GAC), Namati and Grassroots Justice Network members from Argentina, Chile and Mexico are embarked on a multi-year collective learning journey to precisely address the above injustices. How? By exploring how legal empowerment strategies that build the agency of historically marginalized communities to know, use, and shape the law can advance systemic solutions to environmental justice challenges.

In Chile, ONG FIMA is working with indigenous Kawésqar communities and urban residents who are resisting the salmon industry and its environmental impacts in the region of Magallanes.

In Mexico, ProDESC is working with agrarian and indigenous communities in the Yucatán Peninsula who are facing environmental destruction and threats to dispossess them from their lands by public infrastructure and tourism projects, as well as farming industries.

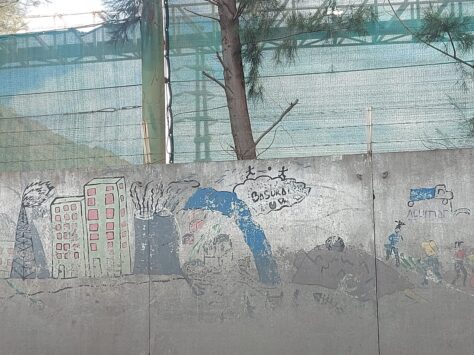

In Argentina, ACIJ is working with informal settlement residents who live next to one of the most polluted waterways in the region (the Matanza-Riachuelo river basin) and for whom environmental impacts in their settlements have become a threat of displacement, or an opportunity to access better housing and other services.

These projects are part of a broader effort within the Grassroots Justice Network known as the Learning Agenda for Legal Empowerment. This collective effort aims to look at the frontiers of the legal empowerment field and generate learning about ‘what works’ across key themes such as how to build community power, how to achieve systemic change, how to measure our impact, and how to stay safe while doing legal empowerment work. Projects in Latin America are connected to a broader cohort of action research projects from different countries in Africa and Asia.

From July 27 to 30, Namati and the Grassroots Justice Network convened the Latin American cohort in Buenos Aires, Argentina, for the first of an annual cycle of in-person meetings.

Below we share a few emerging learnings and takeaways.

Despite three very different contexts, the displacement of communities and dispossession of their land is driven by economic interests hidden behind false pretenses to protect the environment and local communities, as well as so-called ‘public utility’ reasons.

In Argentina, high levels of pollution and lead in blood led to an original mandate to displace residents of certain settlements along the Matanza-Riachuelo river basin (instead of those responsible for the environmental impacts; the industries along the river basin). In the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, authorities at the behest of private corporations are using so-called ‘natural protected areas’ to dispossess communities from their lands and allow for the exploitation of those areas by the tourism sector. In Chile, in the region of Magallanes, capricious distinctions between ‘natural reserves’ and ‘natural parks’ have allowed the salmon industry to operate in the community waters of the Indigenous Kawésqar Peoples and pollute them.

Partners are using a combination of innovative legal empowerment strategies to tackle these challenges.

For example, partners in Mexico are using strategic litigation to stop projects and win time to organize the communities. In Chile, partners are using strategic litigation as an exemplifying mechanism for public policies, to raise awareness about the impacts of the salmon industry, and to engage more members of affected communities in environmental defense. In Argentina, where the lack of implementation of a groundbreaking court resolution is leading community members to view legal strategies as inefficient, partners are opting for greater lobbying and community-led advocacy efforts to put pressure on decision-makers. Across the three countries, partners are also working closely with communities to build their capacities and leadership to demand the guarantee of their rights, and to identify and prevent future threats to their land and natural resources. At the same time, they are also engaging communities in a dialogue about how to counter hegemonic narratives that place them as actors against development and progress.

Women are increasingly leading environmental defense efforts. However, such leadership doesn’t always translate to having a say in decision-making due to different kinds of participation barriers.

In Chile, the ‘Kawésqar Communities for the Defense of the Sea’ with whom FIMA works are mostly represented by female leaders, who have gone through an empowerment journey and now are carrying forward their own administrative actions. In Argentina, the strength of the feminist movement is reflected in the community leadership at informal settlements where ACIJ works: most of the community leaders are women, who also take on other care duties for the neighborhood such as distributing water, or hosting a soup kitchen. However, in both cases they continue to face barriers when it comes to public participation. These are barriers that affect all community members, such as a lack of participation spaces, lack of information about them, or the complexity of decision-makign in those spaces.

On the other hand, in Mexico, where as of 2020 “only 25.9% of the people who had a land title which recognized them as ejidatarias or comuneras were women”, women continue to face barriers to integrate formal community decision-making bodies. Even if they have a leadership role within the community, they might not be able vote in community agrarian assemblies, for example, as they lack land titling. To revert this, ProDESC is working to update the community census and ejidal register to ensure that land tenure rights are passed on to women through inheritance from their fathers and they are progressively integrated as title holders, and, therefore, into community decision-making bodies.

Partners are finding ways to counter the hegemonic narratives in each of their contexts, and build new, positive ones that give voice to the communities’ demands and aspirations.

In the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, ProDESC is working with agrarian indigenous communities to counter the hegemonic narratives driven by economic interests that place these communities as being against the touristic and economic development of the area. Instead, they are building their own narratives about what development and progress means for them. In Chile, FIMA is facing hegemonic narratives that push for so-called ‘green’ energies (such as green hydrogen) as the future of the country, even though these continue to be incompatible with environmental defense. In a context in which there is a progressive government that is generally in support of environmental justice, FIMA is working to make sure that their policies don’t coopt or misappropriate concepts like community participation.

In Argentina, ACIJ’s challenge lies within the very same informal settlement’s community narrative. Since environmental impacts like soil pollution were behind an original mandate to relocate residents in Villa Inflamable, communities now associate environmental issues with displacement. The mandate has been revoked and residents have avoided displacement. However, now, even though the community is aware that their right to live in a healthy environment is not being fulfilled, they are they are hesitant to demand any improvements to their neighborhood due to the fear of such demands leading to displacement.

Stay tuned to hear more about this group and emerging learnings!

SHARE THIS: